Rick Pruetz

RickPruetz@outlook.com

The Virtuous Cycle

Bicycle trails are good for business. They attract restaurants, brewpubs and retail shops catering to those who walk or pedal for fun, exercise, health, and to get from place to place. When trails connect centers of employment, recreation, education and culture, they also generate residential development aimed at people who increasingly prefer active transportation to fighting traffic. And when trails are extended and linked with one another, they expand tourism revenue from a growing breed of vacationers who want to get out of their cars and experience places at a more leisurely and enjoyable speed.

As trails succeed, they increase business activity, employment, wages, property value, income and, importantly, tax revenues in a self-reinforcing upward spiral. Specifically, trail improvements boost trail use which grows trail-adjacent businesses and property investments which, in turn, expand tax revenues and create public support for further trail improvements. By riding bike trails throughout North America, my wife and I got a first-hand look at this virtuous cycle.

The 38 profiles included below primarily explore how communities are using bicycle trails and other cycling infrastructure to attract and grow commercial businesses. But Chapter 1 serves as a reminder that bicycling also reduces healthcare expenses and costs associated with traffic congestion as well as increasing real estate values and generating other economic benefits.

Table of Contents

- Economic Benefits of Bicycling

- A) Reduced cost of transportation benefits local economies

- B) Reduced cost of transportation benefits economic resilience and mobility

- C) Reduced healthcare costs

- D) Increased property value due to proximity of bike infrastructure

- E) Improved transport efficiency benefits

- F) Reduced cost of roadway and parking improvements;

- G) Economic benefits of reduced energy consumption and pollution

- H) Other economic benefits

- Abington – Damascus – Whitetop, Virginia: Saved by the Creeper

- Austin, Texas: Closing Gaps – Opening Opportunities

- Atlanta, Georgia: Economic Development Engine: The BeltLine

- Bentonville-Fayetteville, Arkansas: On the Path to Becoming a World-Class Bicycling Destination

- Boise, Idaho: Gathering at the River

- Caldwell – Cass, West Virginia: Greenbrier River Trail

- Charlotte, North Carolina: Bicycling and the Redevelopment Playbook

- Chattanooga, Tennessee: The Trail to Revitalization

- Chicago, Illinois: Building on a Green Legacy

- Cockeysville, Maryland – York, Pennsylvania: Torrey Brown Trail – Heritage Rail Trail County Park

- Colorado: High on Bicycling

- Covington – Mandeville – Slidell, Louisiana: Tammany Trace Builds Community

- Dayton – Cincinnati, Ohio: Little Miami Scenic Trail Generates Big Results

- Des Moines, Iowa: Expanding Connections and Benefits

- Great Allegheny Passage/C&O Canal Trails: Trails and Trail Towns Are Good for Each Other

- Greenville, South Carolina: The Swamp Rabbit Trail Leads to a Healthy Economy and Lifestyle

- Gulf Coast, Alabama: Snow Birds Flock Here

- Harmony – Lanesboro – Preston, Minnesota: Root River Trail Links Art and Crafts

- Hattiesburg – Prentiss, Mississippi: Adding Spokes to Hub City

- Indianapolis – Carmel, Indiana: Slowing Down Pays Off

- La Crosse – Madison – Milwaukee, Wisconsin: The Route of the Badger

- Louisville, Kentucky: Getting Everyone in The Loop

- Minneapolis, Minnesota: Learning from the Grand Rounds

- Montreal – Quebec, Quebec, Canada: Route Verte – Green in Many Ways

- New Mexico: Gearing Up for Bicycles

- Pittsburgh: From Steel City to Cycle Town

- Portland, Oregon: Bicycling and Portland’s Green Dividend

- Raleigh-Durham, North Carolina: New Roles for the Tobacco Legacy

- South Haven – Kalamazoo, Michigan: Adding Trails to the Tourism Mix

- Sacramento, California: The Great California Delta Trail Promises Great Results

- San Francisco Bay Region, California: The Bay Trail Is Getting Around

- Smyrna, Georgia – Alabama State Line: Silver Comet Trail Keeps Growing

- St. Louis – Sedalia – Kansas City, Missouri: The Katy Trail Is Just the Beginning

- Tallahassee – St. Marks, Florida: Capitalizing on Bicycling

- Tucson, Arizona: Connecting the Dots

- Utah: Seeing the Beauty of Bicycle Tourism

- Vancouver, British Columbia: Copenhagenizing in Canada

- Washington State: Benefiting from Connections

1. Economic Benefits of Bicycling

As detailed in the 38 profiles below, communities increasingly recognize bicycling trails and other cycling infrastructure as an important economic development tool because these improvements support businesses that serve cyclists. In some cases, trail-oriented businesses generate millions of dollars annually in retail sales while growing employment, income and tax revenues (Fulsche 2012).

Statewide – The economic impact of bicycling is sometimes calculated on a statewide basis and occasionally achieves benefits measured in billions of dollars. The State of Washington is ranked as the most bicycle-friendly state in the nation with over 1,240 miles of off-road trails which partly explains the estimate that bicycling contributes over $3.1 billion per year to the state economy of which $113,494,490 represents equipment purchases and the remaining $3 billion comes from trip related expenditures (Earth Economics 2015). Similarly, bicycles annually inject $1.6 billion into the Colorado economy, including $511 million spent on lodging, food, beverages and transportation by bicycle tourists (BBC 2016). A 2010 study concluded that bicycle recreation in Wisconsin approached a billion-dollars of benefit, generating $924 million in economic impacts and supporting 13,191 full-time-equivalent jobs (Grabow, Hahn & Whited 2010).

Although statewide benefits are lower in other states and provinces, they still generate economic impacts greater than a third of a billion dollars. Bicycle tourism in the Canadian province of Quebec generated $700 million in spending in 2015, creating 6,800 jobs and generating $100 million in tax revenues for the Quebec government as well as $38 million for the Canadian government (Velo Quebec 2016). A 2009 study calculated that trail bicycle riding in Minnesota generated $427 million in total spending, supporting 3,736 jobs with employee compensation of $87 million and state and local tax revenues of over $35 million (Venegas 2009). Traveling cyclists spent almost $400 million in Oregon in 2012, supporting 4,630 jobs with a payroll of $102 million and tax receipts of almost$18 million (Dean Runyan Associates 2013). A 2011 study estimated that recreational riders alone contributed $365 million to the Iowa economy (Lankford, J. et al. 2011).

Even states with lower estimated benefits still experience economic impacts in nine figures from cycling and cyclists. A 2012 report estimated that bicycling contributed over $300 million annually to the New Mexico economy in equipment purchases and travel related expenses (Atencio 2012). A 2014 study estimated that bicycles and bicycling add $224 million per year to the Michigan economy:$175 million in retail spending, $38 million on bicycle events and tourism plus$11 million on bike related manufacturing (BBC Research & Consulting 2014). Bicycle tourism in Utah annually produces a total economic impact of $121.9 million in spending, supporting 1,499 jobs with $46.73 million of employment income (Feer & Peers 2017).

Regional Benefit Estimates – Several studies document the benefits of multiple trails on regional economies. Trails in the seven-county Minneapolis metro area were estimated to experience almost 86 million person days of walking, bicycling, running and inline skating in 2008, generating over $487 million in trail spending (Venegas 2009). In 2012, cyclists in the Portland metro area generated $89 million in spending, accounting for 700 jobs, $18.7 million in earnings and $4.1 million in state and local tax revenues (Dean Runyan Associates 2013). The 70 miles of trails that form the spine of the East Coast Greenway in the Raleigh- Durham region of North Carolina generate over $87 million in economic benefits annually and support 800 temporary and permanent jobs (East Coast Greenway Alliance 2017). Similarly, bicycling in Northwest Arkansas contributes $51 million per year to the regional economy including $27 million from the spending of out- of-state bicycle tourists at local businesses throughout the region. (BBC Research & Consulting 2018). The Little Miami Scenic Trail and four other trails in Ohio’s Miami Valley are estimated to generate a total direct economic impact of up to $15.4 million a year for this region (Miami Valley Regional Planning Commission 2017). Similarly, the multiple trails radiating from downtown Des Moines, Iowa are estimated to generate an economic impact of $15 million and support almost 215 jobs (Fleming et al. 2013).

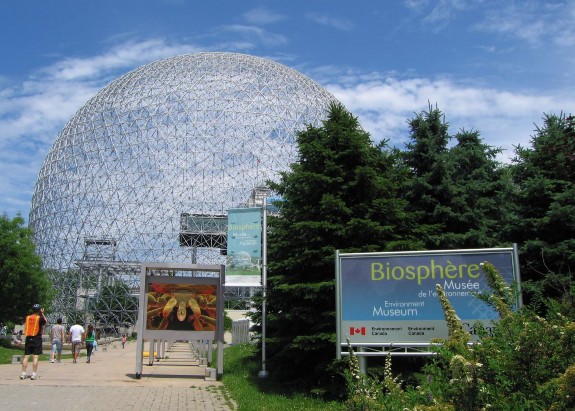

Individual Trail Benefits – As illustrated in the 38 profiles below, studies have also quantified the economic benefit of several individual trails. Some of the most economically-productive trails are longer and anchored by one or more large cities. For example, the 61.2-mile Silver Comet Trail northwest of Atlanta, creates a total annual impact of almost $120 million within the State of Georgia while supporting roughly 1,300 jobs and producing $37 million in earnings plus $3.5 million in income tax, sales tax and business tax revenues (Alta 2013). In 2000, cyclists on Route verte, the 3,100-mile network stretching between and around Montreal and Quebec, spent $64.6 million, supporting 2,000 jobs and generating$15.1 million in tax revenues for the Quebec government as well as $11.9 million for the government of Canada (Velo Quebec 2003). Similarly, the 335-mile Great Allegheny Passage/Chesapeake and Ohio Canal Trail between Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and Washington, DC was estimated to generate an impressive $40 million in direct spending and $7.5 million in wages during 2008 (The Progress Fund 2009).

Many other trails succeed at generating economic benefits in the eight-figure range. The 37-mile long Spokane River Centennial State Park Trail contributes$30 million to the regional economy (Stark 2014). The 240-mile Katy Trail in Missouri annually attracts 400,000 visitors, generating a total impact of $18.5 million to local economies and supporting 367 jobs with a payroll of $5 million (Synergy/PRI/JPA 2012). The 44-mile trail formed by Maryland’s Torrey C. Brown Rail Trail and Pennsylvania’s Heritage Rail Trail County Park generates between $13.5 and $14.4 million per year to the local economies (Knoch 2017; Trail Facts 2005). In fiscal year 2015-16, the 25-mile Tallahassee – St. Marks Trail in Florida produced a total direct economic impact of $13,065,398, generating $890,913 in state sales tax and supporting 209 jobs (Florida Department of Environmental Protection 2016).

Shorter trails in or near major cities often generate economic benefits in the seven-figure range. The 14-mile Butler Trail in Austin, Texas single-handedly attracts 2.6 million visitors annually and generates $8.8 million in economic impact, supporting 88 full-time equivalent jobs, $3.2 million in labor income and almost $200,000 in state and local tax revenue (Angelou Economics 2016). The 17-mile Swamp Rabbit Trail in Greenville, South Carolina annually contributes$6.7 million to local businesses (Maxwell 2014). In Charlotte, North Carolina, the six-mile Sugar Creek Greenway generates over $5.2 million per year in sales revenue, supporting 73 jobs with over $2 million in labor income (North Carolina Department of Transportation 2018).

Regardless of the size of the communities they link, some trails nevertheless generate remarkable economic benefits. The 31-mile Tammany Trace, connecting Covington and Slidell, Louisiana, annually contributes an estimated$7.3 million to local economies (Hammons 2015). The 77-mile Greenbrier River Rail Trail, anchored by Marlinton, West Virginia, population 1,000, annually generates $3.1 million of economic impact, which is a meaningful contribution for a region striving to transition from its lumber mill past (Magnini and Uysal 2015). The 42-mile Harmony-Preston/Lanesboro-Houston Root River system in Minnesota was estimated to be responsible for trip spending of over $2.2 million even though the largest of the four villages linked by this network has a population of less than 1,300 people (Kelly 2010).

This report focuses primarily on the economic benefits that bicycle trails and networks create for trail-oriented businesses in terms of sales, employment, income and tax revenues as briefly sketched above. However, before proceeding directly to the 38 case studies that form the bulk of this report, below are a few reminders that bicycling and cycle infrastructure also produce economic benefits in other ways including the following:

- Reduced cost of transportation benefits local economies;

- Reduced transportation cost benefits to economic resilience and mobility;

- Reduced healthcare costs;

- Increased property value due to proximity of bike infrastructure;

- Improved transport efficiency benefits;

- Reduced cost of roadway and parking improvements;

- Economic benefits of reduced energy consumption and pollution; and

- Other economic benefits.

A. Reduced cost of transportation benefits local economies

The paragraphs above summarize economic benefits of bicycle-oriented business. A slightly different benefit occurs when people have more money to spend on local goods and services because of the savings in transportation costsmade possible by good walking, bicycling and public transport services. Expenditures on cars and fuel typically involve the outflow of money from local economies while reduced auto-dependency generally supports local economies. The less people drive, the less they spend on driving and the more money they have to spend on other things. According to a 2007 study, since Portlanders drive 20 percent less than average Americans, they have an extra $1.1 billion in their pockets, a so-called Portland Green Dividend. Furthermore, by reducing expenditures on cars and gas (which primarily leave the state), this $1.1 billion has a better chance of being spent in economic sectors with higher local multiplier effects including restaurants and brewpubs (Cortright 2007). Of course transit, walking and compact development as well as bicycling account for Portland’s lower auto-dependency. But together, the green dividend concept suggests that Portland’s economy is strong because of, rather than despite, its sustainability successes.

B. Reduced cost of transportation benefits economic resilience and mobility

Good bicycling infrastructure inherently promotes social justice by improving mobility options for families regardless of whether or not they own an automobile. The low-cost option of commuting by bicycling increases employment opportunities and improves the potential for improving household income. In addition, bike-friendly communities improve the ability of employers to attract and retain employees, particularly lower-wage workers without personal automobiles. Therefore the ability to bike to work promotes upward economic mobility for lower-income households and improves the prosperity of the city as a whole.

Several studies confirm that walkable/bikeable cities promote economic resilience – the ability to overcome unanticipated financial reversals including reduced incomes or unexpected expenses (Litman 2020). Walkable cities also advance intergenerational upward economic mobility – the ability of children from lower-income households to move up the economic ladder in adulthood. A 2018 study documented a strong relationship between walkable cities and economic mobility. In these cities, the lack of an automobile is less of a barrier to upward mobility. In fact, the ability to accomplish things without a car was found to be a key factor in upward mobility. In addition to decreased reliance on cars, people living in walkable cities have a greater sense of belonging to their communities, a feeling associated with documented changes in social class (Oishi, Koo and Buttrick 2018).

C. Reduced healthcare costs

Medical costs are lowered by the improved health and fitness created by bicycling, walking and other forms of active transportation. Modern life has taken a toll on the medical condition of many people in the United States and other developed countries. Manufacturing occupations and other active jobs of a generation ago have largely been replaced by desk jobs that entail sitting in a chair and staring at a screen. Auto-dependency has reduced people’s inclination to walk just about anywhere. And now, ride-hailing companies offer door-to-door service, thereby eliminating even the effort of walking to your car. In 2018, less than a quarter of American adults met the guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control for aerobic and muscle-strengthening activity (Centers for Disease Control 2019).

Sedentary lifestyles have created a medical emergency. Half of American adults do not get enough physical activity needed to help reduce and prevent chronic diseases. Not surprisingly, half of all U.S. adults have at least one chronic disease and a quarter have two or more. Adequate physical activity could prevent one-tenth of premature deaths from breast cancer, colorectal cancer, diabetes, and heart disease. In monetary terms, inadequate physical activity is associated with $177 billion in healthcare costs every year. Considering that one-quarter of young adult Americans weights too much for military service, physical inactivity is also considered a risk to defense readiness (Centers for Disease Control 2020).

Walking and bicycling improve healthcare outcomes. A 2017 study involving 263,540 participants in the United Kingdom concluded that commuting on foot reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease and that commuting by bicycle lowers the risk of mortality from all causes and cancer as well as cardiovascular disease (Celis-Morales 2017). Similarly, a 2013 study found that walking lowers the risk of mortality from all causes by up to 20 percent and from cardiovascular disease by up to 30 percent (Sinnett et al 2013).

Several researchers have estimated the monetary value of improved health resulting from walking and cycling. A 2013 study from Australia monetizes the average health benefits of walking at $1.68 per kilometer and the improved healthcare outcome of bicycling at $1.12 per kilometer (Mulley et al 2013). Similarly, a 2008 New Zealand study monetized health benefits as $3 per mile of walking and $1.6 per mile of cycling (Litman 2013).

Another study calculated that shifting trips of five kilometers or less from cars to bicycles for 250 days generates 1,300 euros of health care benefits annually to the rider and 30 euros per year of benefit to all city residents from improved air quality. The health benefit from improved air quality for bicyclists however varies depending on whether the cycling occurs on separate bike paths or on roads shared with motor vehicles (Rabl and de Nazelle 2012).

A study of 11 metropolitan areas in the Upper Midwest of the United States estimated that $8 billion per year in health benefits would result from air quality improvement and increased physical activity if car trips of eight kilometers or less were eliminated and half of all short trips were made by bicycle (Grabow et al, 2012). Similarly, bicycling in Northwestern Arkansas was estimated to generate$86 million in healthcare benefits (BBC Research & Consulting 2018).

The healthcare benefits of cycling are sometimes calculated on a statewide basis. In Michigan, bicycling was estimated to save $256 million in health care costs and $187 million in the cost of work absenteeism as part of a study that found a total annual economic impact of $667 million from cycling (BBC Research & Consulting 2014). In 2011, bicycling was estimated to annually produce $87 million in healthcare savings for the State of Iowa (Lankford, J. et al. 2011).

Some studies take the next step and monetize the healthcare benefits of pedestrian and bicycle infrastructure. A 2011 study analyzed the $138 million to$605 million that Portland had invested and planned to invest in bicycling infrastructure over a 40-year period. It concluded that this investment would save from $388 million to $594 million in healthcare costs alone. This outcome suggested that the disease-fighting results would single-handedly justify expenditures in robust cycling systems. In addition, the statistical value of the lives saved by physical activity on the Portland system was estimated to range from $7 billion to $12 billion, which represents staggering returns on investment(Gotschi 2011). In Austin, Texas, a single bicycle trail was estimated to annually produce $4.3 million of medical cost savings (Angelou Economics 2016).

D. Increased property value due to the proximity of bike infrastructure

A growing portion of the population is demonstrating its preference for walkable/bikeable neighborhoods. In a 2017 survey, the National Association of Realtors found that over half of all Americans prefer to live where they can easily walk to community amenities and believe that walkability contributes to the quality of life (National Association of Realtors 2017).

Walkability can be quantified by Walk Score, a publically-accessible index that rates locations on a scale of 0 to 100 based on pedestrian routes to everyday destinations like schools, parks, grocery stores, restaurants, and retail. In 2012, Walk Score launched a similar program called Bike Score, which rates places from 0 to 100 for bike-friendliness based on bike lane infrastructure, hilliness, the percent of commuting done by bicycle, and the destinations that can easily be reached by bicycle (Walk Score 2020).

In a 2009 study of 15 U.S. cities, home values typically increased from $500 to$3,000 for each Walk Score point (Cortright 2009). A more recent study of 14U.S. major metro areas concluded that every Walk Score point can increase the value of a home 0.9 percent, or $3,250 on average. Despite large variations between real estate markets, this study suggests that real estate prices demonstrate preferences for walkable neighborhoods (Bokhari 2016).

As with walkability, bike trails generally increase the value of the nearby property. A 2008 study reviewed five hedonic studies that used actual property values and found that trails had consistently positive effects for nearby homes. For example, one study found that 14 percent ($13,056) of predicted prices could be attributed to the Monon Rail Trail, the popular 27-mile rail-trail connecting Indianapolis with its northern suburbs. Another study estimated that single-family residential properties increased in value by $7.05 for each foot they are located closer to the Little Miami Scenic Trail in Ohio (Karadeniz 2008). Similarly, homes within a quarter-mile of the Razorback Greenway in Northwest Arkansas were found to sell for $15,000 more on average than comparable homes two miles from the trail (BBC Research & Consulting 2018).

Some research calculates the impact of bicycle trails on the property value of entire regions. A 70-mile stretch of the East Coast Greenway was estimated to add $164 million to regional property value in the Raleigh-Durham Region of North Carolina (East Coast Greenway Alliance 2017). The Silver Comet Trail in Northwest Georgia produced a total value increase of $180 million and additional property tax revenues of over $2 million per year for the jurisdictions and school districts adjacent to the trail (Alta 2013). Similarly, Tucson’s 131-mile Loop trailwas found to add $300 million in tax base, thereby generating more than $3 million per year in extra property tax revenue for this metro area (Pima County 2013).

The redevelopment potential of trail networks is evident in larger cities. The Beltline trail system that will eventually encircle downtown Atlanta is projected to ultimately remediate 1,100 acres of brownfields, build 5,600 affordable housing units, generate $10 to $20 billion in economic development, create 30,000 permanent jobs and support 48,000 one-year construction jobs (Atlanta BeltLine 2018a).

E. Improved transport efficiency benefits

The public right of way theoretically belongs to the entire public. But personal cars occupy much more of this space than pedestrians and cyclists, causing roadways to be congested, inefficient, and unpleasant, even for motorists. Pedestrians and cyclists require less than a quarter of the space consumed by a single occupant vehicle (SOV) traveling 30 kilometers per hour and less than five percent of the pavement needed for an SOV traveling at 60 kilometers per hour (Litman 2000). This difference is unfair to all pedestrians and cyclists but also raises a social justice issue for people who have no options other than walking and cycling.

Walkability and bike-ability reduce auto dependency, consequently lowering traffic congestion and related costs of time delay and accidents. In 2007, congestion was estimated to cost the economy of the United Kingdom 20 billion pounds due to wasted time, pollution caused by inefficient motorized transportation, and various health problems including respiratory diseases and stress-related illnesses. Expanding roadway capacity does not necessarily relieve congestion since increased traffic often overwhelms the new capacity. But switching from cars to bicycling has a quantifiable benefit. A 2007 study estimated that one person switching from car use to cycling for 624 kilometers per year annually reduces the cost of roadway congestion by 68.64 pounds in rural areas and137.28 pounds in urban areas (SQW 2007).

Some studies quantify the monetary benefits from reduced congestion produced by individual bicycling trails. For example, the trail encircling Lady Bird Lake in Austin, Texas is estimated to annually produce $727,103 of traffic reduction benefits (Angelou Economics 2016).

F. Reduced cost of roadway and parking improvements

Due to vehicle weight, size, and speed, the cost of constructing and maintaining infrastructure is much lower for pedestrians and cyclists than motor vehicles. One study estimated that changing from driving to cycling or walking saves five cents per urban mile and three cents per rural mile in terms of infrastructure construction and maintenance (Litman 2020).

The annualized cost of an urban parking space ranges between $500 and $3,000 depending on whether the space is located in a surface parking lot, a multi-level parking structure, or someplace in between. Because ten to 20 bicycles can be stored in a single parking space, switching from cars to bicycles reduces parking costs by 90 to 95 percent (Litman 2020). Since parking bicycles are typically cost-free, increasing the ability to bicycle rather than drive further promotes mobility for people who have no car or who simply would prefer to spend less on transportation and more on other things.

Some business owners resist eliminating on-street parking for bike lanes or bike corrals under the assumption that car drivers are better customers. However, surveys of customers at bars, convenience stores and restaurants in Portland, Oregon, found that although cyclists spend less per visit than motorists, they tend to visit more often and consequently spend almost 25 percent more per month than their car-driving counterparts (Clifton, Morrissey & Ritter 2012).

A study conducted in Davis, California found that cyclists there not only make more trips per month to downtown businesses but that they also spend more per trip and contribute more to local businesses than their car-bound counterparts (Davis 2014). Another study found that the same square meter of parking space in downtown Melbourne, Australia generates over three times more in retail sales per hour when used by bicycles rather than cars for various reasons including higher turnover and the smaller area needed by cycles (Lee and March 2007).

G. Economic benefits of reduced energy consumption and pollution

Switching from motor vehicles to walking and bicycling saves an average of one to four cents per mile in energy costs (Litman 2020). In total, fuel consumption can be reduced by two to four percent for every one percent shift from motor vehicles to active transportation (Komanoff and Roloff 1993).

Motor vehicles generate local impacts, such as noise, particulates, and carbon monoxide, as well as regional and global impacts, including ozone, carbon dioxide, and methane. A review of several studies developed a reasonable conclusion that a driver switching from driving a motor vehicle to walking or cycling reduces these multiple impacts by ten cents per urban mile during peak traffic hours, five cents per mile in urban areas during non-peak hours and one cent per mile in rural areas (Litman 2020).

H. Other economic benefits

The construction of bicycle infrastructure creates more jobs per dollar of investment than the installation of roads for motor vehicles. A study of 58 projects in 11 U.S. cities, found that the construction of bicycling infrastructure creates11.4 full-time-equivalent in-state jobs per $1 million while the construction of road-only projects creates 7.8 jobs per $1 million. The greater job-generation ratios occur because the construction of bicycling infrastructure is more labor-intensive and generally requires less importation of materials from other states (Garrett-Peltier 2011).

Because pedestrians and cyclists consume less urban space than cars, cities that emphasize active transportation can be more compact, diverse and ultimately successful. Compact cities with well-designed, multi-use neighborhoods consume 75 percent less energy and other resources than cities that follow the wasteful, business-as-usual model popular in the late 20th century (International Resource Panel 2017).

REFERENCES: 1 – Economic Benefits of Bicycling

Alta. 2013. Silver Comet Trail: Economic Impact Analysis and Planning Study. Accessed 11-5-19 at http://www.bwnwga.org/wp-content/uploads/Silver_Comet_Combined.pdf.

Angelou Economics. The Trail: Economic Impact Analysis 2016. Accessed 2-6-20 at https://www.thetrailfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/ttf-economic-impact-analysis-2016.pdf.

Atencio, E. 2012. Trails for the People and Economy of Santa Fe. Accessed 2-9-20 at https://sfct.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/Trails-for-the-People-and-Economy-of-Santa-Fe.pdf.

Atlanta Beltline. 2018a. The Atlanta BeltLine: Where Atlanta Comes Together. Accessed on July 13, 2018, from https://beltline.org/about/the-atlanta-beltline-project/atlanta- beltline-overview/.

BBC Research & Consulting. 2014. Community and Economic Benefits of Bicycling in Michigan. Accessed 8-27-19 at https://www.michigan.gov/documents/mdot/MDOT_CommAndEconBenefitsOfBicyclingIn MI_465392_7.pdf.

BBC Research & Consulting. 2016. Economic and Health Benefits of Bicycling and Walking. Denver: Colorado Office of Economic Development and International Trade.

BBC Research & Consulting. 2018. Economic and Health Benefits of Bicycling in Northwest Arkansas. Accessed 3-10-20 at https://www.waltonfamilyfoundation.org/learning/economic-and-health-benefits-of- bicycling-in-northwest-arkansas.

Bokhari, Sheharyar. 2016. How Much is a Point of Walkscore Worth? Accessed 5-30-20 at https://www.redfin.com/blog/how-much-is-a-point-of-walk-score-worth/.

Celis-Morales, Carlos, et. al 2017. Association between Active Commuting and Incident Cardio-Vascular Disease, Cancer, and Mortality: Prospective Cohort Study. Accessed 6- 1-20 at https://www.bmj.com/content/bmj/357/bmj.j1456.full.pdf.

Centers for Disease Control. 2019. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. Accessed 5-29-20 at https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/downloads/trends-in-the-prevalence-of- physical-activity-508.pdf.

Centers for Disease Control. 2020. Physical Activity – Why It Matters. Accessed 5-29-20 at https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/about-physical-activity/why-it-matters.html.

Clifton, J., Morrisey, S. & Ritter, C. 2012. Business Cycles: Catering to the Bicycling Market. Accessed 11-27-19 at http://kellyjclifton.com/Research/EconImpactsofBicycling/TRN_280_CliftonMorrissey&Rit ter_pp26-32.pdf.

Cortright, Joe. 2007. Portland’s Green Dividend. CEOs for Cities. Accessed 6-12-20 at https://forwardcities.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Portland-Green-Dividend- Report.pdf.

Cortright, Joe. 2009. Walking the Walk: How Walkability Raises Home Values in U.S. Cities. Accessed 5-31-20 at https://nacto.org/docs/usdg/walking_the_walk_cortright.pdf.

Davis. 2014. Bicycle Action Plan: Beyond Platinum. Accessed 12-5-19 at http://documents.cityofdavis.org/Media/CityCouncil/Documents/PDF/CDD/Planning/Subdivisions/West-Davis-Active-Adult-Community/Reference- Documents/City_of_Davis_Beyond_Platinum_Bicycle_Action_Plan_2014.pdf.

Dean Runyan Associates. 2013. The Significance of Bicycle-Related Travel in Oregon: Detailed State and Travel Region Estimates, 2012. Accessed 11-26-19 at http://www.deanrunyan.com/doc_library/bicycletravel.pdf.

Earth Economics. 2015. Economic Analysis of Outdoor Recreation in Washington State. Accessed 11-2-19 at https://drive.google.com/file/d/0ByzlUWI76gWVR1Z4SmpIdUZyUWc/view?pref=2&pli=1.

East Coast Greenway Alliance. 2017. The Impact of Greenways in the Triangle: How the East Coast Greenway Benefits the Health and Economy of North Carolina’s Triangle Region. Accessed on August 19, 2018, from https://www.greenway.org/uploads/attachments/cjgqs3ffg03yyp8qitykwkvz8-triangle- impact-report.pdf.

Feer & Peers. 2017. Economic Impacts of Active Transportation: Utah Active Transportation Benefits Study. Accessed 10-28-19 at https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5b8b54d1f407b40494055e8f/t/5bdc820c4fa51a4d 9f77e014/1541177878083/Utah+Active+Transportation+Benefits+Study+-+Final+Report.pdf.

Fleming, K. et al. 2013. The Economic Impact of Des Moines Parks and Recreation Services. University of Northern Iowa. Cedar Falls, IA. file:///C:/Users/Richard/Documents/Prosperity%20economic_impacts_des_moines_park s.pdf.

Florida Department of Environmental Protection. 2016. State Park System Direct Economic Impact Assessment – Fiscal Year 2015-2016 District 1. Tallahassee: Florida Department of Environmental Protection.

Flusche, Darren. 2012. Bicycling Means Business: The Economic Benefits of Bicycle Infrastructure. League of American Bicyclists. Accessed 6-12-20 at https://bikeleague.org/sites/default/files/Bicycling_and_the_Economy- Econ_Impact_Studies_web.pdf.

Garrett-Peltier, Heidi. 2011. Pedestrian and Bicycle Infrastructure: A National Study of Employment Impacts. Political Economy Research Institute: University of Massachusetts, Amherst. Accessed 6-13-20 at file:///C:/Users/Richard/Downloads/PERI_ABikes_October2011%20(1).pdf.

Gotschi, Thomas. 2011. Costs and Benefits of Bicycling Investments in Portland, Oregon. Journal of Physical Activity and Health. Accessed 5-30-20 at https://www.portlandmercury.com/images/blogimages/2011/03/03/1299202929- portland_bike_cost_study.pdf.

Grabow, M., Hahn, M., Whited, M. 2010. Valuing Bicycling’s Economic and Health Impacts in Wisconsin. The Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies. University of Wisconsin – Madison. Accessed 8-20-19 at file:///C:/Users/Richard/Documents/Prosperity%20WI%20Econ%20Grabow%202010.pdf.

Grabow, Maggie, et al. 2012. Air Quality and Exercise-Related Health Benefits from Reduced Car Travel in the Midwestern United States. Accessed g-7-20 at https://ehp.niehs.nih.gov/doi/10.1289/ehp.1103440.

Hammons, Hagen Thames. 2015. Assessing the Economic and Livability Value of Multi-Use Trails: A Case Study into the Tammany Trace Rail Trail in St. Tammany Parish, Louisiana. Master of Community and Regional Planning thesis. University of Oregon Department of Planning, Public Policy and Management. Accessed on July 5, 2018, from https://scholarsbank.uoregon.edu/xmlui/handle/1794/18963.

International Resource Panel. 2017. The Weight of Cities: Resource Requirements of Future Urbanization. Accessed 6-11-20 at https://www.resourcepanel.org/reports/weight- cities.

Karadeniz, Duygu. 2008. The Impact of the Little Miami Scenic Trail on Single Family Residential Property Values. Accessed 6-1-20 at https://www.americantrails.org/files/pdf/LittleMiamiPropValue.pdf.

Kelly, T. 2010. Status of Summer Trail Use (2007-09) on Five Paved State Bicycle Trails and Trends Since the 1990s. Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. Accessed 8- 19-19 at http://files.dnr.state.mn.us/aboutdnr/reports/trails/trailuse.pdf.

Knoch, C. 2015. Three Rivers Heritage Trail 2014 User Survey and Economic Impact Analysis. Accessed 2-14-20 at https://www.railstotrails.org/resourcehandler.ashx?name=three-rivers-heritage-trail- 2014-user-survey-and-economic-impact-analysis&id=5646&fileName=Three-Rivers- Heritage-Trail-Users-SurveyLORES.pdf.

Knoch, C. 2017. Heritage Rail Trail County Park 2017 User Survey and Economic Impact Analysis. Accessed 3-3-20 at https://drive.google.com/file/d/1yWX2yona3hLmSP0ST87SQJ7cClb1519j/view.

Komanoff, Charles, and Cara Roelofs. 1993. The Environmental Benefits of Bicycling and Walking. U.S. Department of Transportation. Federal Highway Administration. Accessed 6-10-20 at https://www.americantrails.org/files/pdf/BikePedBen.pdf.

Lankford, J. et al. 2011. Economic and Health Benefits of Bicycling in Iowa. Sustainable Tourism and Environmental Program, University of Northern Iowa. Cedar Falls, IA. Accessed 8-18-19 at https://headwaterseconomics.org/wp- content/uploads/Trail_Study_74-economic-health-benefits-cycling-iowa.pdf.

Lee, Allison and Alan March. 2007. Bike Parking in Shopping Strips. Accessed 6-13-20 at http://colabradio.mit.edu/wp- content/uploads/2010/12/Value_of_Bike_Parking_Alison_Lee.pdf.

Litman, Todd. 2020. Evaluating Active Transport Benefits and Costs: Guide to Valuing Walking and Cycling Improvement and Encouragement Programs. Victoria Transport Policy Institute. Accessed 5-29-20 at https://www.vtpi.org/nmt-tdm.pdf.

Magnini, V. and Uysal, M. 2015. The Economic Significance of West Virginia’s State Parks and Forests. Accessed 3-9-20 at https://wvstateparks.com/EconomicResearch2015.pdf.

Maxwell. Tonya. 2014. Study confirms Swamp Rabbit Trail is a boon to businesses. Greenville Online. Accessed on August 7, 2018, from https://www.greenvilleonline.com/story/news/local/2014/12/03/official-swamp-rabbit-trail-greenville-travelers-rest-good-businesses-according-recreation-district-study/19837599/

Miami Valley Regional Planning Commission. 2017. Miami Valley Trail User Report. Accessed 9-18-19 at https://www.mvrpc.org/sites/default/files/trail_user_survey_report_2017.pdf.

Mulley, Corrine et.al. 2013. Valuing active travel: Including the health benefits of sustainable transportation in transportation appraisal frameworks. Research in Transportation Business & Management. Accessed 6-2-20 at https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2210539513000023?via%3Dihub.

National Association of Realtors. 2017. Millenials and Silent Generation Drive Desire for Walkable Communities, Say Realtors. Accessed 5-30-20 at https://www.nar.realtor/newsroom/millennials-and-silent-generation-drive-desire-for- walkable-communities-say-realtors.

North Carolina Department of Transportation. 2018. Evaluating the Economic Impact of Shared Use Paths in North Carolina: Final Report. Raleigh: North Carolina Department of Transportation – Division of Bicycle & Pedestrian Transportation.

Oishi, Shigehiro, Minkyung Koo and Nicholas Buttrick. 2018. The socioecological psychology of upward social mobility. American Psychologist. Accessed 6-11-20 at https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2018-63708-001.

Pima County. 2013. The Loop: Economic, Environmental, Community and Health Impact Study. Accessed 11-11-19 at file:///C:/Users/Richard/Documents/Prosperity%20Tucson%20Econ%20Study%20of%20 Loop.pdf.

Rabl, Ari, and Audrey de Nazelle. 2012. Benefits of the shift from car to active transport. Transport Policy. Accessed 6-6-20 at https://www.locchiodiromolo.it/blog/wp- content/uploads/2012/02/science.pdf.

Sinnett, Danielle et al. 2013. Making the Case for Investment in the Walking Environment: A review of the evidence. Accessed 6-1-20 at https://uwe-repository.worktribe.com/output/971643.

SQW. 2007. Valuing the benefits of cycling: A report to Cycling England. Accessed 6-21- 20 at https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20110407101006/http://www.dft.gov.u k/cyclingengland/site/wp-content/uploads/2008/08/valuing-the-benefits-of-cycling- full.pdf.

Stark, L. 2014. Washington’s Centennial Trail State Park – Trail of the Month: February 2014. Accessed 11-2-19 at https://www.railstotrails.org/trailblog/2014/february/01/washingtons-centennial-trail-state- park/.

Synergy/PRI/JPA. 2012. Katy Trail Economic Impact Report: Visitors and MGM2 Economic Impact Analysis. Accessed on 8-17-19 at https://mostateparks.com/sites/mostateparks/files/Katy_Trail_Economic_Impact_Report_ Final.pdf.

The Progress Fund. 2009. The Great Allegheny Passage Economic Impact Study (2997- 2008). Accessed 2-21-20 at file:///C:/Users/Richard/Downloads/GAPeconomicImpactStudy200809%20(1).pdf

Trail Facts. 2005. NCR Trail User Survey and Economic Impact Analysis. Accessed on 3-3-20 at https://www.railstotrails.org/resourcehandler.ashx?id=4792.

Velo Quebec, 2003. Cyclists spend over $95 million CAD (($64 million USD) annually along the Route Verte. Accessed 1-18-20 at http://www.velo.qc.ca/en/pressroom/20030508171603/Cyclists-spend-over-$95-million- CAD-$64.6-million-USD-annually-along-the-Route-verte.

Velo Quebec. 2016. Bicycling in Quebec: 2015. Accessed 1-18-20 at http://www.velo.qc.ca/files/file/expertise/VQ_Cycling2015.pdf

Venegas, E. 2009. Economic Impact of Recreational Trail Use in Different Regions of Minnesota. University of Minnesota Tourism Center, Accessed 8-19-19 at https://conservancy.umn.edu/bitstream/handle/11299/168117/economic%20impact%20o f%20recreational%20trails%202009.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

Walk Score. 2020. Bike Score. Accessed 5-31-20 at https://www.walkscore.com/bike- score-methodology.shtml.

2. Abington – Damascus – Whitetop, Virginia: Saved by the Creeper

In addition to spa treatments, golf rounds, and theater performances, the Martha Washington Inn will shuttle you and your bike to the far end of the Virginia Creeper Trail, allowing a 34-mile ride back to this historic hotel in Abington, Virginia. The ‘Martha’ and many other local businesses are wisely capitalizing on one of the country’s most scenic rail trails and a well-deserved honoree in the Rail-Trail Hall of Fame (Traillink 2018). Bike shops, brewpubs, restaurants, and all forms of lodging have gravitated to the Virginia Creeper both in Abington and Damascus, the aptly-nick-named “Trail Town USA” at the trail’s midpoint. Economic studies have documented that this apparent success story in the heart of the Blue Ridge Mountains is real.

The steam engines that originally used this rail line literally crept up the long, uphill slope from Damascus to Whitetop Station, now the southern trailhead. The grade in this section is definitely noticeable, which is why many visitors choose to shuttle rather than pedal to the top. No fewer than eight outfitters are more than happy to provide this sweat-free uphill lift. The downhill ride is both exhilarating and spectacular, passing waterfalls and crisscrossing mountain streams as the Creeper winds through mile after mile of the Jefferson National Forest. Most riders pause at Green Cove where the original rail station still welcomes visitors with a dose of history and, occasionally, some live local music. Further downhill, it is practically mandatory to stop at the Creeper Trail Café for something cold or hot depending on the weather (Stark 2013).

Arriving in Damascus, riders can taste a locally-crafted concoction from the Damascus Brewery, linger in a cafe or stay the night at any of more than a dozen inns, cottages, or B&Bs. We chose the Damascus Old Mill Inn, which overlooks a waterfall and mill pond teeming with ducks, geese and fishermen. The 2000-plus- mile Appalachian Trail intersects the Virginia Creeper Trail in Damascus and uses the sidewalk on the main street here before climbing back into the hills on the other side of town. Every spring, Damascus hosts Trail Days, attended by roughly 20,000 cyclists, hikers and other nature lovers hoping to catch the rhododendrons and mountain laurels at peak bloom (Stark 2013). Wayne Miller, President of the Virginia Creeper Trail Club, gives the following opinion of the trail’s importance. “Damascus is a little mill town that was saved by the trail. It was on its last legs. The old industries were shutting down. Now it supports eight bike shops that service the trail” (Stark 2013).

Heading north, the scenery changes from forests to farms as cyclists pedal the remaining 17 miles to Abington where they are greeted by a 1907 steam engine tailored to the Creeper’s tight curves, steep grades and wooden trestles (Stark 2013). On bike-friendly Pecan Street, cyclists soon enter the Abington Historic District, listed in the National Register of Historic Places. Here, the previously- mentioned Martha Washington Inn, dating from 1832, was a residence and college before becoming an upscale hotel in 1935. An 1831 building across the street became a theater in 1933 called the Barter Theatre because people could attend plays by bartering fruit and vegetables from their farms and gardens during the depths of the Great Depression. The Barter now welcomes over 120,000 visitors a year with a year-round schedule (Barter Theatre 2013).Further up Main Street, the county still dispenses justice in a courthouse built in 1869 (National Park Service 2018).

In addition to history and bike trails, Abington offers visitors other reasons to hang around including a winery, brewery, art museum, craft stores and art galleries plus several outstanding restaurants like The Tavern, serving traditional German meals in a landmark building that originally housed a stagecoach inn. Kevin Worley, Abington’s Director of Parks and Recreation, is working to get more people on the Creeper for economic as well as health reasons: “They come in to do the Creeper, then come in to do other things in town. The trail brings a lot of economic benefit to the town” (Stark 2013).

Formal economic studies support these personal observations. For his 2004 master’s degree thesis, Joshua Gill conducted an extensive survey of Virginia Creeper users. The survey responses allowed him to estimate the percentage of users who travel here primarily to ride this rail trail. The survey also distinguished between day users and overnight users. For example, of the 39,367 primary- purpose, non-local trips, 33,642 were day trips and 5,725 were overnight trips.The overnight trips involved lodging revenue as well as higher per-trip expenditures on food, bike rentals and shuttles. Consequently, primary-purpose, non-local overnight users were estimated to spend roughly four times more than their day use counterparts. As a bottom line, Gill calculated the Creeper’s total economic impact at $1.6 million per year when applying a multiplier to direct expenditures (Gill 2004).

A 2007 report estimated that 106,000 people used the Virginia Creeper in the study year. The authors calculated that the $1.6 million in total annual economic activity supported 27 jobs and $610,000 in labor earnings. That represents a sizable portion of the local economy considering that Abington had a population of 8,186 and Damascus was home to less than 800 people (Bowker, Bergstrom & Gill 2007).

In 2011, a team from the Virginia Tech Economic Development Studio surveyed local businesses as well as trail users. More than half of the commercial respondents reported that trail use generated over 61 percent of their income.The report concluded that Damascus owes its economic success to trail-based tourism, with many local entrepreneurs naming the Virginia Creeper as a motivation for opening a business here (Economic Development Studio 2011).

As shown by these studies, despite the disappearance of the steam locomotives essential to bygone industries, the Virginia Creeper is still an economic engine.

References: 2 – Abington – Damascus – Whitetop, Virginia: Saved by the Creeper

Barter Theatre. 2013. AbouBarter Theatre. 2013. About. Accessed on July 30, 2018 from https://bartertheatre.com/about/history.

Bowker, J.M., Bergstrom, J., Gill, J. 2007. Estimating the economic value and impacts of recreational trails: a case study of the Virginia Creeper Rail Trail. Tourism Economics.13(2): 241-260.

Economic Development Studio [Stephen Cox, Jonathan Hedrick, Chelsea Jeffries, Swetha Kumar, Sarah Lyon-Hill, William Powell, Katherine Shackelford, Sheila Westfall, Melissa Zilke]. 2011. Building Connectivity Through Recreation Trails: A Closer Look at New River Trail State Park and the Virginia Creeper Trail. Blacksburg: Economic Development Studio – Virginia Tech.

Gill, Joshua. 2004. The Virginia Creeper Trail: An Analysis of Net Economic Benefits and Economic Impacts of Trips. Thesis – Master of Science Degree. Athens: University of Georgia.

National Park Service. 2018. Abington Historic DistrictNational Park Service. 2018. Abington Historic District. Accessed on July 31, 2018 from https://www.nps.gov/nr/travel/vamainstreet/abingdon.htm.

Stark, Laura. 2013. Virginia Creeper National Recreation Trail. American Trails. Accessed on July 30, 2018 from https://www.railstotrails.org/trailblog/2013/may/01/virginia-creeper-national-recreation-trail/.

Traillink. 2018. Virginia Creeper National Recreation Trail. Accessed on Traillink. 2018. Virginia Creeper National Recreation Trail. Accessed on January 6, 2018 at https://www.traillink.com/trail/virginia-creeper-national-recreation-trail/.

3. Austin, Texas: Closing Gaps – Opening Opportunities

Austin thrives in the heart of Texas largely because of water. Logically, much of Austin’s bicycle network follow creeks and surrounds Lady Bird Lake, an impoundment of the Colorado River that gives this city of 950,000 people a picture-perfect foreground for its downtown skyline. Although this network required some expensive gap-closing boardwalks and bridges, the city is doubling down on its investment, knowing that a well-designed bicycle system is good for business as well as mobility, health, recreation and the environment.

Austin is the only city in Texas to be recognized as a Gold Level Bicycle Friendly Community (League of American Bicyclists 2020.) This ranking reflects Austin’s bicycle plan which aims to create a network for all ages and abilities from 8 to 80 years of age. As of 2014, Austin already had a 210-mile bicycle network linking neighborhoods, schools, parks, greenspace and public institutions as well as employment and commercial centers (Austin 2014).

Part of this system is formed by 16 greenbelt trails that generally follow creeks flowing down to Lady Bird Lake (Austin 2020a). On the west side of downtown, the 6.8-mile Shoal Creek Greenbelt Trail connects five parks and passes Austin Community College, with 60,000 total enrollment, before merging with other trails at Shoal Beach on the north shore of Lady Bird Lake. Northeast of the Texas state capitol building, Waller Creek bisects the University of Texas campus, home to the Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library. Further downstream, the Waller Creek Greenbelt Trail, connects several parks and neighborhoods before ending at Waller Beach on Lady Bird Lake.

Austin’s 85 hike-and-bike trails total 125 miles in length (Austin 2020a). Although most of these trails are short, the network has remarkable exceptions. At the northern end of the eight-mile Barton Creek Greenbelt Trail, Zilker Park is home to a botanical garden, a nature preserve, a science center and a miniature railroad. Further south, the trail passes Barton Springs Pool, a three-acre, outdoor swimming pool fed entirely by natural spring water which annually attracts 800,000 visitors. Further up Barton Creek, mountain bikers can climb the trail into Barton Creek Wilderness Park, the largest of 15 nature preserves in Austin’s 2,200-acre nature preserve system (Austin 2020b).

The crown jewel of Austin’s trail system is the 14-mile Ann and Roy Butler Trail which now forms a complete loop around Lady Bird Lake thanks to the closing of a 1.3-mile gap in 2014 using a $28-million complex of boardwalks and bridges over the water (Austin 2020c). Traveling counter-clockwise from Festival Beach, cyclists can pedal the Butler Trail though a continuous park system lining the north shore of the lake. On one of four possible options, cyclists can ride the Pfluger Pedestrian and Bicycle Bridge to reach the south side of Lady Bird Lake at an entertainment complex that includes a performing arts center, a theater, and an outdoor concert space.

Continuing east on the Ann and Roy Butler Trail, riders can stop to rent boats, kayaks and paddleboards or simply take a break at a restaurant patio overlooking the lake. After navigating the boardwalk and bridges, the trail enters 400-acre Roy G. Guerrero Colorado River Metro Park featuring a wildlife sanctuary as well as volleyball courts, softball diamonds, fitness stations, and Secret Beach, a sandy, shallow stretch of river where kids can splash in a natural wading pool.

The Butler Trail alone attracts 2.6 million visitors annually and generates $8.8 million in economic impact, supporting 88 full-time equivalent jobs, $3.2 million in labor income and almost $200,000 in state and local tax revenue. A 2016 study found that monthly rental rates increase by $0.28 per square foot of office floor area for every quarter-mile of proximity to the trail. That study also estimated that the trail annually produces $495,182 of environmental benefits, $727,103 of traffic reduction benefits and $4.3 million of medical cost savings (Angelou Economics 2016).

Economic return is one reason why Austin’s bicycle plan proposes 220 miles of on-street facilities and 150 miles of off-street urban trails. Implementation of this plan carries a price tag of $161 million. But Austin recognizes that this investmentwill benefit mobility, congestion management, health and the environment as well as the local economy (Austin 2014).

References: 3 – Austin, Texas: Closing Gaps – Opening Opportunities

Angelou Economics. The Trail: Economic Impact Analysis 2016. Accessed 2-6-20 at https://www.thetrailfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/ttf-economic-impact-analysis-2016.pdf.

Austin. 2014. 2014 Austin Bicycle Plan. Accessed 2-6-20 at https://austintexas.gov/sites/default/files/files/2014_Austin_Bicycle_Master_Plan__Reduced_Size_.pdf.

Austin. 2020a. Trail Directory. Accessed 2-7-20 at http://www.austintexas.gov/page/trail-directory.

AustinAustin. 2020b. Nature Preserves and Nature Based Programs. Accessed 2-7-20 at https://austintexas.gov/naturepreserves.

Austin. 2020c. Ann and Roy Butler Hike and Bike Trail and Boardwalk at Lady Bird Lake. Accessed 2-7-20 at http://www.austintexas.gov/department/ann-and-roy-butler-hike-and-bike-trail.

League of American Bicyclists. 2020. Bicycle-Friendly Communities. Accessed 2-6-20 at https://bikeleague.org/sites/default/files/bfareportcards/BFC_Fall_2015_ReportCard_Austin_TX.pdf.

4. Atlanta, Georgia: Economic Development Engine: The Belt Line

Ladybird Grove & Mess Hall proclaims its address as Mile Marker 9.5 on the Atlanta Beltline. That’s one measure of the success of this city’s ambitious project to redevelop and connect 45 neighborhoods encircling downtown using the conversion of 22 miles of abandoned rail corridors as the catalyst. Ladybird Grove owes much of its popularity to its quirky, summer camp vibe and huge selection of craft beer. But the main attraction here is a huge deck overlooking the Beltline where people can take a break from their walking, running, or biking and watch others passing by under their own non-motorized power.

Proximity to the Beltline is in high demand. “Beltline Living” is a common advertising slogan seen on the banners hanging from new apartment buildings under construction here. Taking its cue from Ladybird Grove, a beer garden facing the Beltline was nearing completion when we pedaled past in 2018.Anchoring the Eastside Trail is Ponce City Market. Once a Sears & Roebuck regional distribution center built in the 1920s, this two million square-foot building has been repurposed as a multi-use complex with 259 apartment units, 550,000 square feet of office space and 330,000 square feet of retail including a Central Food Hall featuring famous chefs and international cuisine. Ponce City Marketincorporates bike storage, showers, and bike-friendly elevators in order to take maximum advantage of its location on the Beltline (Urban Land Institute 2016).

In 1999, the Beltline concept was first proposed in a thesis written by Ryan Gravel, a Georgia Tech graduate student. Grassroots support for the idea was nurtured by Friends of BeltLine and a 2004 Trust for Public Land study demonstrating the feasibility of the project using a Tax Allocation District (TAD). By 2005, a plan and TAD were approved and the first trail segment was open by 2008 (Atlanta BeltLine 2018b). As of 2016, the project had created seven parks and hundreds of affordable housing units as well as $3 billion in residential complexes, commercial buildings, affordable housing and other forms of private investment (Atlanta BeltLine 2018a).

The Beltline is all about connecting Atlanta. While the Atlanta region is famous for sprawl, the older parts of the city of Atlanta concentrate many recreational, cultural, residential and commercial destinations within easy bicycling distance via the Beltline. The Eastside Trail segment of the Beltline passes through 185- acre Piedmont Park. In 1887 and again in 1895, this park was the site of international expositions, two of many reasons why the park is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Some elements from this era still survive, including Lake Clara Meer, which once featured water slides and diving platforms. A 1912 Olmstead Brothers plan influenced the park’s current look, which offers the Atlanta Botanical Garden, a swimming pool, a tennis academy,ball fields, playgrounds, dog parks, a community garden and a Saturday morning farmers’ market (Piedmont Park Conservancy 2018).

Just south of Ponce City Market, a consortium has transformed an area previously plagued by flooding and neglect into the Historic Fourth Ward Park, a model of multi-functional green infrastructure. This 17-acre park includes a playground, splashpad, skatepark, sport areas, and passive green space. In addition, the two-acre lake here serves as a storm water detention basin as well as a stunning bit of landscape architecture (Atlanta BeltLine 2018a).

On a spur called the Freedom Park Trail, cyclists can pedal one mile west to the Martin Luther King Jr. National Historical Park. The Visitor Center here explores the life of Dr. King and the Civil Rights Movement. Surrounding the Center are Dr. King’s birth home, grave and the Historic Ebenezer Baptist Church, where Dr. King was co-pastor from 1960 until his death in 1968 (National Park Service 2016).

Just east of the Beltline on Freedom Park Trail, cyclists encounter the 35-acre campus of the Carter Center, a non-governmental organization founded by former US President Jimmy Carter promoting conflict resolution, civil rights, democracy, disease prevention and mental health. The beautifully landscaped grounds here showcase a particularly-moving sculpture depicting a child leading a man stricken with river blindness, a disease that the Carter Center and its partners are in the process of eradicating throughout the world (The Carter Center 2018). Visitors to the Carter Presidential Library & Museum can take selfies in a life-size replica of the Oval Office and wander through a maze of exhibits on the life and times of Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter, with understandable emphasis on 1977 through 1981, the turbulent four years of the Carter Presidency (Jimmy Carter Library 2018).

Going further east, the Freedom Park Trail becomes the Stone Mountain Trail and a trail spur leads to Dinosaur Plaza, an outdoor space in front of the Fernbank National History Museum dominated by a family of Lophorhothon atopus dinosaurs recreated in bronze. The 75 acres surrounding the museum are home to Fernbank Forest, the largest old-growth Piedmont forest within the urban United States. In the heart of the city, hikers can wander two miles of paths beneath trees more than 16-stories tall. The WildWoods exhibit features an elevated walkway where visitors can experience forest life from a treetop perspective (Fernbank 2018).

The destinations sketched above are connected by the Eastside Trail, one of four segments of the Beltline that are currently in use. On completion in 2030, the Beltline will connect 2,400 acres of parkland with a 22-mile streetcar loop and 33 miles of multiuse trails. Atlanta BeltLine estimates that the project will ultimately remediate 1,100 acres of brownfields, build 5,600 affordable housing units, generate $10 to $20 billion in economic development, create 30,000 permanentjobs and support 48,000 one-year construction jobs (Atlanta BeltLine 2018a). Considering the huge success of the Beltline segments finished so far, these estimates might actually be conservative.

References: 4 – Atlanta, Georgia: Economic Development Engine: The Belt Line

Atlanta Beltline. 2018a. The Atlanta BeltLine: Where Atlanta Comes Together. Accessed on July 13, 2018 from https://beltline.org/about/the-atlanta-beltline-project/atlanta- beltline-overview/.

Atlanta BeltLine. 2018b. Project History. Accessed on July 15, 2018, from https://beltline.org/progress/progress/project-history/.

Fernbank 2018. Fernbank Museum of Natural History. Accessed on July 15, 2018, from http://www.fernbankmuseum.org/explore/permanent-features/.

Jimmy Carter Library. 2018. Museum. Accessed on July 15, 2018, from https://www.jimmycarterlibrary.gov/museum.

National Park Service. 2016. Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Park. Accessed on July 14, 2018, from https://www.nps.gov/malu/index.htm.

Piedmont Park Conservancy. 2018. History. Accessed on July 14, 2018, from https://www.piedmontpark.org/park-history/.

The Carter Center. 2018. About. Accessed on July 15, 2018, from https://www.cartercenter.org/.

Urban Land Institute. 2016. Active Transportation and Real Estate: The Next Frontier. Washington, DC: The Urban Land Institute.

5. Bentonville-Fayetteville, Arkansas: On the Path to Becoming a World-Class Bicycling Destination

Arkansas may not be the first place you would expect to find a bike trail linking five cities within a 132-mile regional network. But the Razorback Regional Greenway officially opened in Northwest Arkansas in 2015 and it is already demonstrating that investments in bicycle infrastructure pay off in terms of wealth as well as health and happiness. As you would expect, the jurisdictions are responding to this success by making further trail expansions.

The Razorback Regional Greenway is a 37-mile bikeway spine linking the cities of Bentonville, Rogers, Lowell, Springdale and Fayetteville. According to a prominent bicycle infrastructure planning firm: “The project serves as a national model for active transportation, green infrastructure, healthy living, sustainable economic development, and public-private partnerships” (Alta Planning + Design 2017 P14). The partnership included the Walton Family Foundation and the U.S. Department of Transportation with assistance from the Northwest Arkansas Regional Planning Commission and local governments (Alta Planning + Design 2017).

Although considered as a single trail, the Razorback Greenway is actually a chain of 19 linked trails, beginning at Bella Vista Lake near the northern city limits of Bentonville (Rail-to-Trails Conservancy 2020). Bentonville is home to six segments of the Razorback Greenway, eight additional intra-city trails plus several miles of planned trails (Bentonville 2020). Not surprisingly, Bentonville has been recognized as a Bicycle Friendly Community by the League of American Bicyclists. As an indication of the success of the Razorback Greenway, the League has also given its Bronze level ranking to Springdale and its Silver level ranking to Fayetteville as well as the two-county Northwest Arkansas region (League of American Bicyclists 2020).

In Bentonville, the Razorback Greenway passes through the Crystal Bridges complex, which includes an art museum, performance center, and sculpture garden enclosed within nature-inspired architecture designed by Moshe Safdie. The grounds are also home to the Bachman- House, an example of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Usonian design which he developed as a model for affordable American housing. In addition to art and architecture, visitors can explore nature on eight trails within Crystal Bridges including a hiking trail leading to Crystal Springs, the natural spring that gave this complex its name (Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art 2020).

The next 7.4 miles of the Razorback Greenway cruise through the City of Rogers, a city that already has 27 other trails and plans to complete a 60-mile network connecting parks, schools, commercial centers, and neighborhoods with one another as well as the regional trail system (Rogers 2020).

After a short stretch through the City of Lowell, the Razorback travels for nine miles through Springdale, passing the Shiloh Historical District listed in the National Register and the Shiloh Museum of Ozark History, which celebrates the pioneer past of the region in general and Springdale in particular, which was originally named Shiloh (Shiloh Museum of Ozark History 2020). From the Razorback Greenway, a connecting trail leads to the Jones Center, a multi- purpose fitness/recreation center featuring ice skating, swimming and a bike park designed to train riders for the growing popularity of mountain biking in the region (Jones Center 2020). Nearby, the 10,000-seat Rodeo of the Ozarks has been doing all things cowboy and cowgirl since 1944 (Rodeo of the Ozarks 2020).

In Fayetteville, the Razorback Greenway is part of a 40-mile system of paved, shared-use trails. A six-mile segment encircles Lake Fayetteville, a 458-acre, in- city park for boating and fishing. This loop also serves the Botanical Garden of the Ozarks, a 44-acre greenspace that attracts 80,000 visitors a year with 12 separate gardens and the only native butterfly house in the region (Botanical Garden of the Ozarks 2020).

Further south in Fayetteville, the Greenway intersects with Dickson Street, a lively entertainment district featuring performance venues like the Walton Arts Center and George’s Majestic Lounge which claims to be the longest-running club and live music stage in Arkansas. Turning west, the Razorback intersects with the bike network of the University of Arkansas, famous for championship teams and for the four-mile-long Senior Walk inscribed with the names of more than 170,000 graduates of the university, and counting (University of Arkansas 2020).

Cyclists are responding to the expansion of bike trails in Northwest Arkansas. In the two years following completion of the Greenback Greenway in 2015, annual bicycle counts rose by 24 percent. In terms of cyclists per 1,000 population, Northwest Arkansas ranked between Portland, Oregon and San Francisco, California in 2017 (Walton Family Foundation 2017).

Another study proves that investments in trails here are paying off. Bicycling in general contributes $137 million per year in health and economic benefits to Northwest Arkansas. Of this amount, health benefits represent $86 million, and the other $51 million are business benefits. Of that $51 million, $21 million is generated by resident spending on bicycles, bicycling equipment, and events while $27 million annually comes from the spending of out-of-state bicycle tourists at local businesses throughout the region. The study also documents that entrepreneurs want to locate their establishments near the Razorback, primarily to attract customers but also to improve visibility and facilitate access for employees as well as customers. In addition, the study found that homes within a quarter mile of the Razorback Greenway sell for $15,000 more on average than comparable homes two miles from the trail (BBC Research & Consulting 2018).

The Razorback Trail was officially completed in 2015 but the expansion of Northwest Arkansas trails continues. The Regional Bicycle and Pedestrian Master Plan proposes trail interconnections between and within 32 jurisdictions in Benton and Washington counties with the aim of making Northwest Arkansas a “…world-class bicycle and pedestrian destination” (NWA Regional Planning Commission 2015, ES1). These communities are accepting that challenge. For example, the City of Bella Vista, located between Bentonville and the Arkansas – Missouri border, announced in 2018 that it was doubling the length of its natural- surface, multi-use trails, creating a 100-mile network with help from the Walton Family Foundation (Bella Vista 2018). As shown by the 2017 studies mentioned above, the Razorback and other trails in the region are promoting health, economic vitality, eco-mobility, and, ultimately, public demand for more trails. Just another good example of the virtuous cycle.

References: 5 -Bentonville-Fayetteville, Arkansas: On the Path to Becoming a World-Class Bicycling Destination

Alta Planning + Design. 2017. Trail Program Implementation: A Peer + Aspirational Review. Accessed 3-10-20 at https://www.waltonfamilyfoundation.org/learning/trail-program-implementation-a-peer-aspirational-review.

BBC Research & Consulting. 2018. Economic and Health Benefits of Bicycling in Northwest Arkansas. Accessed 3-10-20 at https://www.waltonfamilyfoundation.org/learning/economic-and-health-benefits-of- bicycling-in-northwest-arkansas.

Bella Vista. 2018. New 50-mile Trail System Announced for Bella Vista. Accessed 3-21- 20 at https://www.bellavistaar.gov/news_detail_T12_R69.php.

Bentonville. 2020. Paved Trails and Road Rides. Accessed 3-11-20 at https://www.visitbentonville.com/bike/trail-maps/paved/.

Botanical Garden of the Ozarks. 2020. Accessed 3-10-20 at https://www.bgozarks.org/.

Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art. Accessed 3-11-20 at https://crystalbridges.org/.

Fayetteville. 2020. Paved Shared-Use Trails. Accessed 3-10-20 at http://www.fayetteville-ar.gov/3486/Paved-Shared-Use-Trails.

Jones Center. 2020. Accessed 3-11-20 at https://www.thejonescenter.net/.

League of American Bicyclists. 2020. Bicycle Friendly Communities. Accessed 3-11-20 at https://bikeleague.org/bfa/awards.

Northwest Arkansas Regional Planning Commission. 2015. Walk Bike Northwest Arkansas: Regional Bicycling and Pedestrian Plan – Executive Summary. Accessed 3- 11-20 at http://www.nwabikepedplan.com/final-plan-and-documents.html.

Rodeo of the Ozarks. 2020. About. Accessed 3-11-20 at http://www.rodeooftheozarks.org/about-us.

Rogers. 2020. Our Trails. Accessed 3-11-20 at http://rogersar.gov/211/Our-Trails.

Rails to Trails Conservancy. 2020. Razorback Regional Greenway. Accessed 3-10-22 at https://www.traillink.com/trail/razorback-regional-greenway/.

Shiloh Museum of Ozark History. 2020. Accessed 3-11-20 at https://shilohmuseum.org/.

Walton Family Foundation. 2017. Northwest Arkansas Trail Usage Monitoring Report.Accessed 3-10-20 at https://www.waltonfamilyfoundation.org/learning/northwest-arkansas-trail-usage- monitoring-report.

University of Arkansas. 2020. Senior Walk. Accessed 3-10-20 at https://registrar.uark.edu/graduation/senior-walk.php.

6. Boise, Idaho: Gathering at the River

In 1964, a planning consultant proposed that Boise create a continuous greenbelt of public land along the banks of the Boise River. By 1967, a grassroots campaign had been launched to clean up the previously-neglected waterway and benefactors had donated three parcels of land as the nucleus of the trail. Today, the greenbelt offers 25 miles of riverside pathways, connecting dozens of Boise’s most important civic and recreational venues. In addition to providing a pleasant way to commute, exercise, and enjoy nature, the city also recognizes the greenbelt as an important economic development asset.

The greenbelt evolved from earlier efforts to restore and manage the Boise River itself. In the first half of the 20th century, the river was an unnavigable maze of shallow, shifting channels dotted with debris-strewn islands. Floods periodically swept through the valley, prompting the Army Corps of Engineers to build the Lucky Peak Dam in 1955, which helped carve a single channel and control flow, particularly when the river was swollen by snowmelt and heavy rains (Boise State University 2014).

Prior to 1949, the city allowed dumps to be located on the banks of the river and used its waters for the disposal of raw sewage. But, after two failed attempts, the voters finally passed a bond to build the city’s first sewage treatment plant and the Boise City County prohibited dumping except at approved landfills. The river changed from a contaminated eyesore to a treasured asset, prompting the Jaycees to hold its first “Keep Idaho Green” raft race in 1959. Since then, locals and visitors flock to the river for the tubing and rafting season. Boise’s Parks & Recreation Department now manages the Boise Whitewater Park featuring a wave-shaping dam that adjusts to create ideal conditions for kayakers and surfers. Today, bicyclists on the greenbelt often see fly fisher-persons in chest- high waders angling in what is now considered one of the finest urban trout streams in the country. (Boise Parks & Recreation Department. 2019; Boise State University 2014; Idaho Department of Fish and Game. 2019a).

At the center of the greenbelt, the Anne Frank Human Rights Memorial creates an outdoor classroom dedicated to respect for human dignity and diversity. Heading east on the north side of the Boise River, cyclists encounter Julia Davis Park, one of several riverside parks in Boise’s ‘Ribbon of Jewels’ and home to Zoo Boise, the Boise Art Museum, the Idaho State Historical Museum, the Discovery Center of Idaho and the Idaho Black History Museum. Further east, the Morrison Knudsen Nature Center features an underwater viewing window for visitors to peek in on the river’s aquatic life. Next is the natatorium with an elaborate enclosed slide known as the Hydrotube.

Past the golf course in Warm Springs Park, cyclists can continue to Marianne Williams Park, cross over to the south side of the river at Barber Park, where rafts can be rented and launched for a float down the river. After five miles, cyclists approach Boise State University, home to 22,000 students, the nationally-famous Broncos football team, and the bright-blue artificial turf adorning the playing field within 36,000-seat Albertsons Stadium. At one time, this campus turned its back to the river. But in 1977, a bike-pedestrian bridge to Julia Davis Park strengthened the university’s connection with the greenbelt. In 1984, the riverfront formed the entrance to the Morrison Center, a 2,000-seat theater called Idaho’s Premier Performing Arts Theater (Boise State University 2014).

In another mile, the greenbelt bisects Ann Morrison Park, the take-out point for raft and tube float trips, and Katheryn Albertson Park, with walking loops through urban wildlife habitat. Further west, the Riverside Hotel has taken maximum advantage of its location on the greenbelt, offering restaurants and live-music venues including the Sand Bar, situated directly on the trail and overlooking the river.

In another mile, the southern leg of the greenbelt enters Garden City, which approved extending the trail through the town in 1988. In the next jurisdiction, the City of Eagle, the greenbelt steers clear of Eagle Island State Park in an effort toreduce impacts on birds and other wildlife. This park is part of the Idaho Birding Trail encompassing 20 miles of the river in and around Boise that is home to waterfowl, water birds, shorebirds, song birds and raptors, including Bald Eagles (Idaho Department of Fish and Game. 2019b).

Turning back east on the north side of the river, the greenbelt traverses the Willow Lane Park and Athletic Complex and Veterans Memorial Park before entering Esther Simplot Park, a 55-acre park with 23-acres of ponds suitable for fishing, wading, and swimming. After another mile and another park, cyclists are back where they started at the Anne Frank Human Rights Memorial.

In addition to greenway extensions, Boise and its neighbors are supplementing existing bike lanes and bike-friendly streets with corridors designed to improve safety using new intersection configurations and rider-activated warning signals. By 2021, the Ada County Highway District plans to complete an additional bicycle corridor to Camel’s Back Park in Boise’s North End (Berg 2018). These spurs link the greenway with neighborhood parks, playgrounds, and community facilities including Jack’s Urban Meeting Place, or JUMP, equal parts experimental art studio, creative space, educational center, and tractor museum (JUMP 2019).

Idaho recognizes trails like the Boise Greenbelt is vital to the state’s tourism industry. Roughly ten percent of Idaho vacationers hike or bike during their visits. In 2012, biking and hiking tourists contributed $500 million to Idaho’s economy. By 2035, the state plans to add 650 more miles of shared-use paths, creating a branded 1,000-plus-mile system aimed at attracting more than 1.2 million new users annually and adding $135 million per year in new tourist revenue (Idaho 2014).